This is a shortened version of a diagnostic test for the Boot Camp. All questions are from the College Board website. College Board has full length practice tests as well as individual practice questions for the different sections of the SAT.

Directions:

Select an answer (A-E) for each of the questions below and keep a record of your choices. When you reach the last question, click on the link at the bottom. Fill out your name and answers on the survey and click submit. If you would like to fill out the answers as you go, click here to open the survey in a new tab.

There are only seven questions. Try your best on each question, but if you get stuck on one for a while, guess and move on to the next. You can use a calculator on the math questions.

Question 1: Identifying Sentence Errors

-

Read the entire sentence carefully but quickly, paying attention to underlined choices (A) through (D).

-

Select the underlined word or phrase that needs to be changed to make the sentence correct. Some sentences contain no error at all.

Question 2: Improving Paragraphs

-

Read the entire essay quickly to determine its overall meaning. The essay is intended as a draft, so you will notice errors.

-

Choose the best answer from among the choices given, even if you can imagine another correct response.

The question below is based on the following passage:

(1) Many times art history courses focus on the great “masters,” ignoring those women who should have achieved fame. (2) Often women artists like Mary Cassatt have worked in the shadows of their male contemporaries. (3) They have rarely received much attention during their lifetimes.

(4) My art teacher has tried to make up for it by teaching us about women artists and their work. (5) Recently she came to class very excited; she had just read about a little-known artist named Annie Johnson, a high school teacher who had lived all of her life in New Haven, Connecticut. (6) Johnson never sold a painting, and her obituary in 1937 did not even mention her many paintings. (7) Thanks to Bruce Blanchard, a Connecticut businessman who bought some of her watercolors at an estate sale. (8) Johnson is finally starting to get the attention that she deserved more than one hundred years ago. (9) Blanchard now owns a private collection of hundreds of Johnson’s works — watercolors, charcoal sketches, and pen-and-ink drawings.

(10) There are portraits and there are landscapes. (11) The thing that makes her work stand out are the portraits. (12) My teacher described them as “unsentimental.” (13) They do not idealize characters. (14) Characters are presented almost photographically. (15) Many of the people in the pictures had an isolated, haunted look. (16) My teacher said that isolation symbolizes Johnson’s life as an artist.

In context, which is the best revision to the underlined portion of sentence 3 (reproduced below)?

They have rarely received much attention during their lifetimes.

Question 3: Improving Sentences

-

Read the entire sentence carefully but quickly and ask yourself whether the underlined portion is correct or whether it needs to be revised.

-

Read choices (A) through (E), replacing the underlined part with each answer choice to determine which revision results in a sentence that is clear and precise and meets the requirements of standard written English.

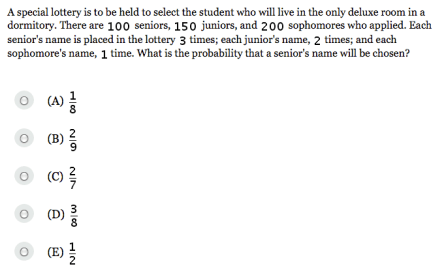

Question 4: Math Multiple Choice

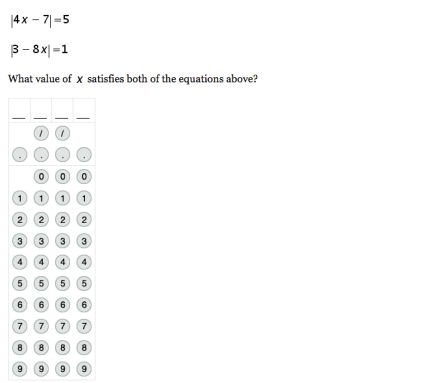

Question 5: Math Student-Produced Responses

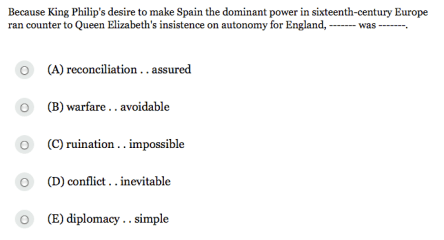

Question 6: Sentence Completion

-

Read the sentence

-

Choose the word or set of words that, when inserted in the sentence, best fits the meaning of the sentence as a whole.

Question 7: Passage-Based Reading

-

Read the passage carefully.

-

Decide on the best answer to each question, and then read the explanation for the correct answer.

This passage is adapted from a novel written by a woman in 1899. The novel was banned in many places because of its unconventional point of view.

Following are sample questions about this passage. In the actual test, as many as thirteen questions may appear with a passage of this length.

You may be asked to interpret information presented throughout the passage and to evaluate the effect of the language used by the author.

Passage

| It was eleven o’clock that night when Mr. Pontellier returned from his night out. He was in an excellent humor, in high spirits, and very |

|

| Line 5 | talkative. His entrance awoke his wife, who was in bed and fast asleep when he came in. He talked to her while he undressed, telling her anecdotes and bits of news and |

| Line 10 | gossip that he had gathered during the day. She was overcome with sleep, and answered him with little half utterances. He thought it very discouraging |

| Line 15 | that his wife, who was the sole object of his existence, evinced so little interest in things which concerned him and valued so little his conversation. |

| Line 20 | Mr. Pontellier had forgotten the bonbons and peanuts that he had promised the boys. Notwithstanding, he loved them very much and went into the adjoining room where they |

| Line 25 | slept to take a look at them and make sure that they were resting comfortably. The result of his investigation was far from satisfactory. He turned and shifted |

| Line 30 | the youngsters about in bed. One of them began to kick and talk about a basket full of crabs. Mr. Pontellier returned to his wife with the information that Raoul |

| Line 35 | had a high fever and needed looking after. Then he lit his cigar and went and sat near the open door to smoke it. Mrs. Pontellier was quite sure |

| Line 40 | Raoul had no fever. He had gone to bed perfectly well, she said, and nothing had ailed him all day. Mr. Pontellier was too well acquainted with fever symptoms to be mistaken. |

| Line 45 | He assured her the child was burning with fever at that moment in the next room. He reproached his wife with her inattention, her habitual neglect of |

| Line 50 | the children. If it was not a mother’s place to look after children, whose on earth was it? He himself had his hands full with his brokerage business. He could not be in two |

| Line 55 | places at once; making a living for his family on the street, and staying home to see that no harm befell them. He talked in a monotonous, insistent way. |

| Line 60 | Mrs. Pontellier sprang out of bed and went into the next room. She soon came back and sat on the edge of the bed, leaning her head down on the pillow. She said nothing, and |

| Line 65 | refused to answer her husband when he questioned her. When his cigar was smoked out he went to bed, and in half a minute was fast asleep. Mrs. Pontellier was by that time |

| Line 70 | thoroughly awake. She began to cry a little, and wiped her eyes on the sleeve of her nightgown. She went out on the porch, where she sat down in the wicker chair and began |

| Line 75 | to rock gently to and fro. It was then past midnight. The cottages were all dark. There was no sound abroad except the hooting of an old owl and the everlasting |

| Line 80 | voice of the sea, that broke like a mournful lullaby upon the night. The tears came so fast to Mrs. Pontellier’s eyes that the damp sleeve of her nightgown no longer |

| Line 85 | served to dry them. She went on crying there, not caring any longer to dry her face, her eyes, her arms. She could not have told why she was crying. Such experiences as the |

| Line 90 | foregoing were not uncommon in her married life. They seemed never before to have weighed much against the abundance of her husband’s kindness and a uniform |

| Line 95 | devotion which had come to be tacit and self-understood. An indescribable oppression, which seemed to generate in some unfamiliar part of her consciousness, |

| Line 100 | filled her whole being with a vague anguish. It was like a shadow, like a mist passing across her soul’s summer day. It was strange and unfamiliar; it was a mood. She did |

| Line 105 | not sit there inwardly upbraiding her husband, lamenting at Fate, which had directed her footsteps to the path which they had taken. She was just having a good cry all to herself. The |

| Line 110 | mosquitoes succeeded in dispelling a mood which might have held her there in the darkness half a night longer. The following morning Mr. |

| Line 115 | Pontellier was up in good time to take the carriage which was to convey him to the steamer at the wharf. He was returning to the city to his business, and they would not |

| Line 120 | see him again at the Island till the coming Saturday. He had regained his composure, which seemed to have been somewhat impaired the night before. He was eager to be |

| Line 125 | gone, as he looked forward to a lively week in the financial center. |

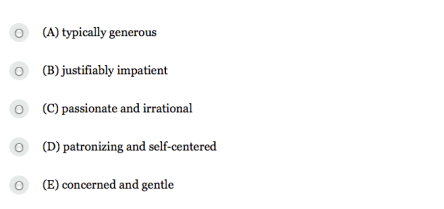

The narrator would most likely describe Mr. Pontellier’s conduct during the evening as